"Only a Poor Old Man"

Good news, everyone! Using Science, I have determined that the first-ever Uncle Scrooge adventure is a pretty good story!

…

What, you're not impressed by my penetrating insight? JEEZ, you're impossible to please. Sometimes I don't know why I bother; I really don't.

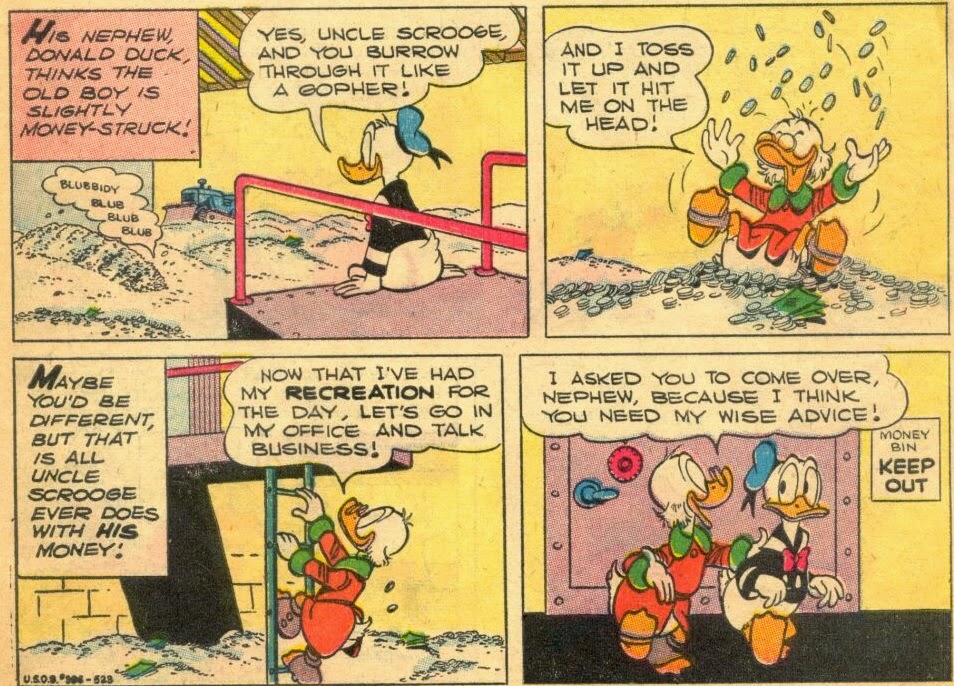

There's really no overstating the story's impact. Most of this stuff isn't new, exactly: we had seen Scrooge bathing in money as far back as "Voodoo Hoodoo:"

We'd known for some time that he had piles of money lying around:

And of course, "The Big Bin on Killmotor Hill" established the bin itself:

Nor did the idea of Scrooge playing with his money come ex nihilo; in "The Big Bin" he is, if not swimming in it, at least kind of wallowing:

That's all neither here nor there, though. Nothing can dull the impact of the way that all these disparate elements that had been brewing for the last few years just come together in "Poor Old Man," creating something potent and entirely new. All changed, changed utterly: a terrible beauty is born. Or something. You get the really, really palpable sense that Barks was very conscious that he was responsible here for the start of a whole new line, and he wanted to do it right: really establish who the character was and what the stakes were. And to go back to the swimming thing for a moment: that was just a brilliant innovation, for the way it lets us palpably feel Scrooge's physical pleasure in his money. Obviously, you couldn't swim in money in real life, as the Beagles learn the hard way (and if you could, it would be really unhygienic), but it's really easy to imagine what it would feel like, isn't it? Even though it wouldn't actually feel anything like that? It's hard to identify with the travails of a centrifugillionaire, and Barks was very wise not to even try to make Scrooge anything like a normal rich guy and make us sympathize with him on normal-rich-guy terms. It's a dynamic that many other writers could've stood to take to heart.

Surprisingly violent stuff, too: maybe I'm wrong--I don't know if that's meant to be some specific sort of fifties trap I'm not aware of--but Scrooge appears to have decapitated that poor rodent, right on-panel. Maybe this is emblematic of the kind of artistic upheaval that the story represents. Sacrifice must be made!

Now, this stuff may not be exactly subtle, but…it actually is kind of subtle of Barks not to go so far as to have the characters actually articulate the point here--pure showing-not-telling. Also, let it be said that this is maybe my favorite aspect of Donald ever. You don't see it in too many stories (though this isn't the last time Barks would use it--see, eg, my little avatar to the right there), but I find the understated, amused irony just priceless. Donald contains multitudes; why shouldn't there be a little wisdom in there in addition to everything else? So, so often--in Barks and elsewhere--Donald is just portrayed as jealous of Scrooge, and plotting to get money from him by means fair or foul. And that's okay--there's certainly plenty of potential there--but here, we see a more complex and interesting dynamic to their relationship. The thing is--as this story makes abundantly clear--Scrooge's money isn't actually money in any standard, economic sense (the fact that Barks keeps using made-up words to talk about how much of it he has may be a clue). That being the case, it only makes sense that their relationship should not always proceed as though it were--as though arguing about it qua money actually made sense. And besides, although this oft goes unrecognized, Scrooge really is a profoundly ambiguous character, and it's extremely useful for him to have someone else as a counterpoint--someone who doesn't just accept his weltanschauung as a given. In stories where Donald is competing with Scrooge over money, there's a sense that while they may be in competition, they're both in general agreement over the rules of the game: more money equals better. But while that's true for Scrooge (though, again, recognizing that "money" for him doesn't mean what it does for a normal person), it's just not for Donald, even if he sometimes thinks otherwise. That's something that's easy to lose track of.

Since Scrooge's salient characteristic--miserliness--is, in itself, so simple, it's easy to just caricature him. Even the most talented writers have done it. But situating this miserliness as nothing more than "people squabbling over money?" Mmm…I dunno. If that's all you're going for, you might as well just watch any reality TV show ever. No reason we shouldn't expect more from our ducks, who are, after all, Mythic.

It goes without saying that this story is the entire backbone of Rosa's Life & Times. Honestly, between this and "Back to the Klondike," you have pretty much the whole thing, minus a bit here and there (okay, better add "The Fantastic River Race"). Still, in all fairness, it has to be admitted…as much as we enjoy Rosa's work, "Poor Old Man" reeeeeally doesn't support his notion that Scrooge didn't begin accumulating his fortune until his Klondike days.

Does anyone honestly think we can reasonably append "…and then, I gave up all that copper money" here? 'Course, I'm not trying to say that this matters or anything. That's one of the main things about myths: there are all kinds of variations on them.

And, of course, although Barks and everyone else constantly contradict that "every bit of money means something" thing, it's still a very powerful concept, and it really drives home the notion--if we hadn't gotten it already--that the importance of Scrooge's fortune has nothing to do with spending power.

Now let me say this: it seems to be pretty much universally accepted that "thirty cents an hour" is meant to represent "extreme cheapness." Only…I realized as I was rereading this story that I'm really not convinced that's true, or at least entirely true, here. Yes, thirty cents an hour is kind of cheap. The minimum wage in 1952 (the internet tells me) was seventy-five cents an hour. But Donald and the kids certainly don't act as though they think they're being exploited (there's never any indication that they wouldn't be helping him even if they weren't being paid--Scrooge offers to compensate them of his own accord), and we had just seen Scrooge articulating his now-famous "and I made it square" mantra. I think Barks is trying to square the circle, a bit--to make Scrooge seem cheap, but not (even if it goes against his instincts) unfairly cheap.

And that is what I have to say about that.

Did I mention how much I love Donald in this story? Well, let me mention it again. "Sounds like great stuff!" truly brings me an incalculable amount of glee.

More violence. The Beagle Boys blowing up fish? That seems pretty inhumane even by their standards. It's worth noting that these guys are no pushovers in this story. They don't lose because they're incompetent. They're damned competent; they only lose because Scrooge is just that slightest bit more so. That's something that Rosa and others have gotten a bit wrong over the years. A mythic hero demands mythic enemies. You don't want Hector to die because he trips and falls on Achilles' sword, dammit. Actually, you probably don't want Hector to die period, but you know what I mean. Your hero will not seem very impressive if he doesn't have villains to match. That was one of the things that annoyed me about "Terror of the Transvaal."

See? Incompetents would probably not have been able to--apparently at will!--just stick a story in the paper and have it look official.

Okay, so there was never any chance that Scrooge would lose here. Nonetheless: another impressive aspect of the story is the way Barks limns his hero's mortality. It's right there in the title, of course, and here again: the terrifying acknowledgement that Scrooge is old and could very easily simply be worn out. Of course, Confronting One's Own Mortality isn't exactly a jolly topic for the kids, and it has to be handled with a light touch. Still, I think recognizing and to one extent or another acknowledging the idea that Scrooge Is Old And He Could Die lends--not to keep pounding this button--a real mythic quality to the proceedings. In his essay on "Horsing Around with History," Geoffrey Blum quotes several times from Tennyson's "Ulysses," which I think is highly appropriate, and not just as a gloss on the nonagenerian Barks.

And I guess I would be remiss if I didn't make note of what may well be Barks' most impressive image ever? It may not be my favorite--not in a world with dueling steamshovels--but it's a helluva thing, no question.

I MEAN JEEZ--the progression here--Scrooge walking into the sunset, mourning lost time, and then having a sudden internal revelation and regaining his resolve without articulating as such--is just dazzling. How the HELL could Barks be that good? How could ANYONE?

And truly, Scrooge's non-explanation for his money-swimming ability is one of the funniest things there is.

Look at Donald kicking Scrooge there, and with no consequences whatsoever: how often do we see anything like that happen? This goes back to what I was talking about regarding Scrooge's money not really being "money" in a literal sense: there's this unspoken idea in many if not most later stories that, because Scrooge has more money than Donald, he's more powerful, and thus can end things by chasing him away with his cane. Here, we see a picture more realistic and more in keeping with the nature of the character. And I suppose I don't even need to mention how much I love love love the way that both Donald and Scrooge are one hundred percent correct in their assessments.

Donald's right: Scrooge's whole character is fundamentally absurd, and the problems in which he embroils his nephews are really irritating for no easily justifiable reason. And yet…there's a deeper level on which Donald and HDL are simply unable to understand their uncle.

Scrooge is right: his money-related frolicking does bring him a kind of joy his nephews can't understand. And yet…there's still the sense that he's living in the past, and in spite of having family who love him in their own grudging way, he still experiences a kind of isolation that Donald never does (it's not irrelevant that he alone occupies those last five panels, and that stunned expression on his face in the fourth panel is in reaction to something real). And this character was expected to appeal primarily to kids. Can you imagine?

This, mes amis, is genius.

There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail:

There gloom the dark, broad seas. My mariners,

Souls that have toil'd, and wrought, and thought with me—

That ever with a frolic welcome took

The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed

Free hearts, free foreheads—you and I are old;

Old age hath yet his honour and his toil;

Death closes all: but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods.

The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks:

The long day wanes: the slow moon climbs: the deep

Moans round with many voices. Come, my friends,

'T is not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

It may be that the gulfs will wash us down:

It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles,

And see the great Achilles, whom we knew.

Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho'

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

…

What, you're not impressed by my penetrating insight? JEEZ, you're impossible to please. Sometimes I don't know why I bother; I really don't.

There's really no overstating the story's impact. Most of this stuff isn't new, exactly: we had seen Scrooge bathing in money as far back as "Voodoo Hoodoo:"

We'd known for some time that he had piles of money lying around:

And of course, "The Big Bin on Killmotor Hill" established the bin itself:

Nor did the idea of Scrooge playing with his money come ex nihilo; in "The Big Bin" he is, if not swimming in it, at least kind of wallowing:

That's all neither here nor there, though. Nothing can dull the impact of the way that all these disparate elements that had been brewing for the last few years just come together in "Poor Old Man," creating something potent and entirely new. All changed, changed utterly: a terrible beauty is born. Or something. You get the really, really palpable sense that Barks was very conscious that he was responsible here for the start of a whole new line, and he wanted to do it right: really establish who the character was and what the stakes were. And to go back to the swimming thing for a moment: that was just a brilliant innovation, for the way it lets us palpably feel Scrooge's physical pleasure in his money. Obviously, you couldn't swim in money in real life, as the Beagles learn the hard way (and if you could, it would be really unhygienic), but it's really easy to imagine what it would feel like, isn't it? Even though it wouldn't actually feel anything like that? It's hard to identify with the travails of a centrifugillionaire, and Barks was very wise not to even try to make Scrooge anything like a normal rich guy and make us sympathize with him on normal-rich-guy terms. It's a dynamic that many other writers could've stood to take to heart.

Surprisingly violent stuff, too: maybe I'm wrong--I don't know if that's meant to be some specific sort of fifties trap I'm not aware of--but Scrooge appears to have decapitated that poor rodent, right on-panel. Maybe this is emblematic of the kind of artistic upheaval that the story represents. Sacrifice must be made!

Now, this stuff may not be exactly subtle, but…it actually is kind of subtle of Barks not to go so far as to have the characters actually articulate the point here--pure showing-not-telling. Also, let it be said that this is maybe my favorite aspect of Donald ever. You don't see it in too many stories (though this isn't the last time Barks would use it--see, eg, my little avatar to the right there), but I find the understated, amused irony just priceless. Donald contains multitudes; why shouldn't there be a little wisdom in there in addition to everything else? So, so often--in Barks and elsewhere--Donald is just portrayed as jealous of Scrooge, and plotting to get money from him by means fair or foul. And that's okay--there's certainly plenty of potential there--but here, we see a more complex and interesting dynamic to their relationship. The thing is--as this story makes abundantly clear--Scrooge's money isn't actually money in any standard, economic sense (the fact that Barks keeps using made-up words to talk about how much of it he has may be a clue). That being the case, it only makes sense that their relationship should not always proceed as though it were--as though arguing about it qua money actually made sense. And besides, although this oft goes unrecognized, Scrooge really is a profoundly ambiguous character, and it's extremely useful for him to have someone else as a counterpoint--someone who doesn't just accept his weltanschauung as a given. In stories where Donald is competing with Scrooge over money, there's a sense that while they may be in competition, they're both in general agreement over the rules of the game: more money equals better. But while that's true for Scrooge (though, again, recognizing that "money" for him doesn't mean what it does for a normal person), it's just not for Donald, even if he sometimes thinks otherwise. That's something that's easy to lose track of.

Since Scrooge's salient characteristic--miserliness--is, in itself, so simple, it's easy to just caricature him. Even the most talented writers have done it. But situating this miserliness as nothing more than "people squabbling over money?" Mmm…I dunno. If that's all you're going for, you might as well just watch any reality TV show ever. No reason we shouldn't expect more from our ducks, who are, after all, Mythic.

It goes without saying that this story is the entire backbone of Rosa's Life & Times. Honestly, between this and "Back to the Klondike," you have pretty much the whole thing, minus a bit here and there (okay, better add "The Fantastic River Race"). Still, in all fairness, it has to be admitted…as much as we enjoy Rosa's work, "Poor Old Man" reeeeeally doesn't support his notion that Scrooge didn't begin accumulating his fortune until his Klondike days.

Does anyone honestly think we can reasonably append "…and then, I gave up all that copper money" here? 'Course, I'm not trying to say that this matters or anything. That's one of the main things about myths: there are all kinds of variations on them.

And, of course, although Barks and everyone else constantly contradict that "every bit of money means something" thing, it's still a very powerful concept, and it really drives home the notion--if we hadn't gotten it already--that the importance of Scrooge's fortune has nothing to do with spending power.

Now let me say this: it seems to be pretty much universally accepted that "thirty cents an hour" is meant to represent "extreme cheapness." Only…I realized as I was rereading this story that I'm really not convinced that's true, or at least entirely true, here. Yes, thirty cents an hour is kind of cheap. The minimum wage in 1952 (the internet tells me) was seventy-five cents an hour. But Donald and the kids certainly don't act as though they think they're being exploited (there's never any indication that they wouldn't be helping him even if they weren't being paid--Scrooge offers to compensate them of his own accord), and we had just seen Scrooge articulating his now-famous "and I made it square" mantra. I think Barks is trying to square the circle, a bit--to make Scrooge seem cheap, but not (even if it goes against his instincts) unfairly cheap.

And that is what I have to say about that.

Did I mention how much I love Donald in this story? Well, let me mention it again. "Sounds like great stuff!" truly brings me an incalculable amount of glee.

More violence. The Beagle Boys blowing up fish? That seems pretty inhumane even by their standards. It's worth noting that these guys are no pushovers in this story. They don't lose because they're incompetent. They're damned competent; they only lose because Scrooge is just that slightest bit more so. That's something that Rosa and others have gotten a bit wrong over the years. A mythic hero demands mythic enemies. You don't want Hector to die because he trips and falls on Achilles' sword, dammit. Actually, you probably don't want Hector to die period, but you know what I mean. Your hero will not seem very impressive if he doesn't have villains to match. That was one of the things that annoyed me about "Terror of the Transvaal."

See? Incompetents would probably not have been able to--apparently at will!--just stick a story in the paper and have it look official.

Okay, so there was never any chance that Scrooge would lose here. Nonetheless: another impressive aspect of the story is the way Barks limns his hero's mortality. It's right there in the title, of course, and here again: the terrifying acknowledgement that Scrooge is old and could very easily simply be worn out. Of course, Confronting One's Own Mortality isn't exactly a jolly topic for the kids, and it has to be handled with a light touch. Still, I think recognizing and to one extent or another acknowledging the idea that Scrooge Is Old And He Could Die lends--not to keep pounding this button--a real mythic quality to the proceedings. In his essay on "Horsing Around with History," Geoffrey Blum quotes several times from Tennyson's "Ulysses," which I think is highly appropriate, and not just as a gloss on the nonagenerian Barks.

And I guess I would be remiss if I didn't make note of what may well be Barks' most impressive image ever? It may not be my favorite--not in a world with dueling steamshovels--but it's a helluva thing, no question.

I MEAN JEEZ--the progression here--Scrooge walking into the sunset, mourning lost time, and then having a sudden internal revelation and regaining his resolve without articulating as such--is just dazzling. How the HELL could Barks be that good? How could ANYONE?

And truly, Scrooge's non-explanation for his money-swimming ability is one of the funniest things there is.

Look at Donald kicking Scrooge there, and with no consequences whatsoever: how often do we see anything like that happen? This goes back to what I was talking about regarding Scrooge's money not really being "money" in a literal sense: there's this unspoken idea in many if not most later stories that, because Scrooge has more money than Donald, he's more powerful, and thus can end things by chasing him away with his cane. Here, we see a picture more realistic and more in keeping with the nature of the character. And I suppose I don't even need to mention how much I love love love the way that both Donald and Scrooge are one hundred percent correct in their assessments.

Donald's right: Scrooge's whole character is fundamentally absurd, and the problems in which he embroils his nephews are really irritating for no easily justifiable reason. And yet…there's a deeper level on which Donald and HDL are simply unable to understand their uncle.

Scrooge is right: his money-related frolicking does bring him a kind of joy his nephews can't understand. And yet…there's still the sense that he's living in the past, and in spite of having family who love him in their own grudging way, he still experiences a kind of isolation that Donald never does (it's not irrelevant that he alone occupies those last five panels, and that stunned expression on his face in the fourth panel is in reaction to something real). And this character was expected to appeal primarily to kids. Can you imagine?

This, mes amis, is genius.

There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail:

There gloom the dark, broad seas. My mariners,

Souls that have toil'd, and wrought, and thought with me—

That ever with a frolic welcome took

The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed

Free hearts, free foreheads—you and I are old;

Old age hath yet his honour and his toil;

Death closes all: but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods.

The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks:

The long day wanes: the slow moon climbs: the deep

Moans round with many voices. Come, my friends,

'T is not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

It may be that the gulfs will wash us down:

It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles,

And see the great Achilles, whom we knew.

Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho'

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

Labels: Carl Barks

16 Comments:

This wasn't the first story to show Scrooge swimming in his money: "Billions to Sneeze At" 3.4-5 and "A Financial Fable" 3.5-7 and 10.5-7 preceded it.

I recently made a list of all Barks' stories that say something about the amount of money Scrooge owns (mostly a good excuse to reread a lot of great stories) and I see you corrected me, because I thought "You Can't Guess" 21.1-3 was the first story with Scrooge bathing in money.

http://bb.mcdrake.nl/neddisney/viewtopic.php?p=64264#p64264

The trapped rat seems quite alive to me. I think it just prevents the animal to withdraw its head. Of course Scrooge does kill spiders and moths.

It's a plesure to read such fine review of such fine story :)

This story holds up remarkably well given that it, like much of Barks's work, has been used as a template for numerous very mediocre stories by other authors (and sometimes Barks himself). And I say that as someone who only read it as an adult - but when I read it I recognised patterns from other stories I'd read in the Donald magazine since I was a kid. I think it really comes down to a sense of wonder that Barks approaches Scrooge's character with: As he introduces his odd habits, he does so with creativity, analysation and understanding of the character that no imitation could ever allow for.

If there's such a thing as a perfect comic, it'd be this. Not a hitch or a misstep. A lovely analysis.

I think you're wise to mark that Barks is not remarking that there is but one way to live. But Donald is wrong on one key element, I think. In the end, Scrooge wants the fruits of his labor. To earn, to have and to hold, to treasure his... treasure. The Beagle Boys want money. I posit that Donald doesn't see, or know, that there is a distinction between the two. While it is clear to the reader, much of what we see and understand of Scrooge's love of the money is shown either in soliloquy, or to the nephews. A very different argument is presented to Donald. Comfort, safety, security, all of those things ARE happiness! Diving in money is presented as a cheap pleasure, rather than bathing in the memories of the past. The feel in the act of earning is never spoken of to Donald, at least not that I recall.

One wonders how long it took for Donald to understand his uncle. Whether he ever came to the realization at all. And whether, as certain Rosa stories suggested, he looked at Scrooge with a kind pity. After all... no matter the story or hijinks, he could always quit.

Regarding the Barks/Rosa canon, such as there is, I have always believed Scrooge's love of each coin faded after he found Donald and the boys in his life again. They certainly mattered. "The Coin", one of Rosa's best, shows that. But he could finally, finally, learn to let some of the old memories go, so long as new ones were there to be made.

This story is so beautifully simple, but it is so easy to talk about at length. A thousand times over, I will call Carl Barks a genius for his work, and point to this as one of his highlights.

What a wonderful story. DUCKTALES filleted it for "Liquid Assets" and a fair bit of the original's power still managed to come through.

Chris

Geo:

As one writer / blogger / would-be Disney comics historian to another… This may simply be the BEST piece you’ve ever written!

You’ve just taken a story about which countless words have been written – over DECADES – and given us a new, fresh, and most importantly, well-written commentary on it!

As to why this is all the more impressive to someone like me, who operates in a similar arena, is to consider (for example) that I’ve written a fair number of Humphrey Bogart movie DVD reviews for my blog – but would never touch the true classics like “Cassablanca” or “The Maltese Falcon”.

Why? It’s certainly not because I’m disinterested in the films, or don’t have the DVDs. It’s because I don’t feel as if I can add anything of significance to the “…countless words [which] have been written – over DECADES”. Instead, I’ll merely upturn some semi-fresh earth on lesser known films like “The Two Mrs. Carrolls” or “Chain Lightning”, about which far less has been written. It’s simpler that way!

Or, to take it closer to home, I may choose to introduce Mickey Mouse stories such as “Rumplewatt the Giant” or “Mickey’s Rival” in the series of Floyd Gottfredson hardcover books from Fantagraphics, rather than those better covered historically – because I can say something more original about them. Again, not because I’m so cleverly creative – but because there’s been far less extant material on those particular stories to contend and compete with.

But you, my friend, have just done a clever, informative – and ORIGINAL – piece on one of the most oft-covered tales in Disney comic book history! Take a bow!

Jakarta must be agreeing with you!

Thanks, Joe. That really means a lot. I think it helped that, while I know perfectly well that this is one of the most famous stories ever, I am unable currently to call to mind or to hand anything that Geoffrey Blum (eg) has written about it, so there was no choice but to strike out on my own. And, of course, I knew in the back of my mind that it would be necessary to dig a little deeper than usual for anything I wrote to justify its existence. Let's also give some credit to Mr. Barks himself, for writing such a rich, multi-layered story. It's sure easier to find something cogent to say about "Only a Poor Old Man" than "The Flying Farm Hand," I'll tell you that much. :)

Now, will I be able to find the stones one of these days to work up an essay on "Back to the Klondike?" That remains to be seen!

I really like your ‘literary’ analysis of this story, Geo. There really should be more of these.

Only now do I appreciate this story on a deeper level. I’ve always found it a cracking yarn, but I’ve been taking a bit of a break from Disney comics because I thought there wasn’t much of a deeper level. I mean yes, I have read some commentaries on Barks stories, in specific and in general, but few of them go this deep. This one shows really well at what level these stories work, especially the whole thing Barks has with money.

So congratulations – you’ve reached new heights in blogging.

It also makes me wonder whether other Barks stories could be examined in this way. I personally prefer the genre stories, ‘Old California’, ‘Shacktown’, ‘Dangerous Disguise’ and all that, but this essay (if I may call it that) has given me a fresh way to look at this story.

If I may add my two cents: I’ve always found it very hard to like the general idea of this story, because it suffers incredibly from thousands of Scrooge stories being based on it. Which really is a testament to the strength of this story, but it’s also harder to see the uniqueness it had back in 1952.

I slightly prefer ‘Klondike’ to this story, though, for the little peek it gives us into Scrooge’s past. There’s just one thing in that story that I find really glaring and gives potential for other stories, but nobody ever comments on. Rosa’s opinion is that ‘the month in the shack’ is the last time Scrooge and Goldie meet before ’40 years later’ (seriously Barks, what the math?). But just look at all that Scrooge remembers from their time together, all just fighting and yelling, and ‘now’ Scrooge utterly falls for her. Rosa interprets this as, well, ‘Prisoner of White Agony Creek’, but I have my own story...

Yes, as others have already said, terrific post, GeoX! I love it when you make me appreciate Barks's artistic subtleties, as when you point out that Scrooge never articulates his bright idea (nor even the fact that he got a bright idea, with an "Oh!" or the like) in the walking-into-the-sunset sequence. Such respect Barks had for his child readers! I also like the fact that it's precisely a memory of an "old trick" that gives the old man victory.

And I love the expression on Donald's face that goes along with that "understated, amused irony" you so appreciate. That sidelong smile!

Thanks, everyone. I hope that future posts can live up to this one--though it's in part dependent on the quality of the stories themselves, o' course.

This is a great analysis. Thank you!

"Does anyone honestly think we can reasonably append "…and then, I gave up all that copper money" here? "

Well... I do. I also think it's reasonable to assume that Scrooge would NEVER mention that part. What does seem a bit unreasonable though, is the fact that he STILL has that coin. Sure, he might not have had to give up ALL the money, but it still seemed like he gave up enough to have had to spend the rest in order to move around/eat/excavate gold. But, who knows, maybe he always kept the first coin earned from each of his failed ventures in his chest. I never quite understood how all that "keeping every coin" fits in with actually EARNING more and becoming the richest duck. (Another musing, is he actually the richest PERSON in the world, or just the richest DUCK ? Hmm... They do seem to use the word "duck" in place of "man/woman" most of the time, but in that world "duck" is just a race)

Is there something to be said about rats' close relationship to mice and the killing of one taking place in the first issue for a character who surely exceeds Mickey in the Disney universe?

Nah, that's probably going too far.

Maybe not, but it's fun to think about!

A real classic. Even as a little child, I always loved older characters who seemed to have history behind them... SO my favourite characters were Scrooge, Captain Haddock, Hercule Poirot, aaand Väinämöinen and Louhi. (So you can imagine Rosa's Kalevala-adventure is fangirling gold for me!)

"Sounds like great stuff!" Thanks to the internet we now know that this is called a "shit-eating grin". You gotta love how much Donald is milking that troll smile thorough this whole tale.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home